admin

29

Aug

Constance Critique no. 5

- By admin

Reflections on Painting with Weather

Essay by Miriam McGarry / Exhibition by Catherine Woo

Photography: Raef Sawford

Painting with Weather is an exploration of natural forces, collaboration with environment, and realisation of ‘process as practice’. Catherine Woo dances between disorder and control to co-create her striking and raw plates.

From the street outside the gallery, visitors can glimpse through a peephole in the tissue-paper lined windows, into the studio space filled with pots, jars, and technical apparatus. Woo’s exhibition Painting with Weather is co-informed by process and resolved ‘product’. This is partly elucidated within the exhibition through the display of Woo’s technical drawings, but the viewer cannot fully comprehend the extent of her method without viewing the adjacent studio where the artist has been working since January.

Woo’s practice is a combination of labour, accident, experiment, surprise, and orchestration- a meeting between control and natural forces. The artist interacts with natural phenomena to create her luminescent and highly tactile weathered surfaces. Painting with Weather does not attempt to achieve a representation or recreation of the weather, and nature writer Robert Macfarlane describes the impossibility of articulating environmental elements,

Natural forces- wild energies- often have the capacity to frustrate representation. Our most precise descriptive language, mathematics, cannot fully account for or predict the flow of water down a stream, or the movements of a glacier or the turbulent rush of wind across uplands. Such actions behave in ways that are chaotic: they operate according to feedback systems of unresolvable delicacy and intricacy[1]

Instead, Woo explores the intra-active collaboration between artist and environment. The process is elemental in a literal sense, as rainwater from outside the gallery is redirected into the studio space, and captured by Woo’s equipment. Through this plumbing intervention into the studio, her practice re-subjects the viewer to the wildness just outside of the gallery walls, and reminds us of societies increasingly distant relationship with the physicality of environmental elements.

Woo channels environmental forces into the studio, and then agitates or de-activates these natural processes on aluminum plates. In this process, Woo is both present and absent. Her practice is part witness/observer to the weather inside her studio, and part as intervener in natural energies. Using the shishi odoshi (a Japanese device used to scare deer with a sudden influx of water), Woo creates miniature floods on her canvas landscapes, but relinquishes control over the effects her deluge will create. This lack of control enhances and enables the collaborative partnership between artist and weather, which Woo describes as an ‘orchestration of unpredictability’ (Interview with the artist).

The relationship between art and science is similarly collaborative and co-constitutive in Woo’s practice. In some respects, the artist takes on a role of apothecary- mixing up solutions: oxides, pigment, sand, and silica. Curator Polly Dance described Woo’s almost ‘ritualistic’ process of changing into her studio outfit, and a peek through the window reveals a well-worn pair of Blundstone boots. However, at the same time, Woo’s practice is informed by a scientific rigor. There is a precision in the way she speaks of her practice, the technical apparatus used, and the experimental methodology she employs. The scientific process of experimentation facilitates opportunities for surprise outcomes, beautiful discrepancies, and accidental divergences.

Woo’s scientific process is documented through notebook extracts pinned to the wall of the gallery Foyer Space, which explicate the methodology behind the striking works. The aluminum plates are coated with calcium carbonate, pigment, and glass beads. Through the display of her notebooks as part of the resolved exhibition, Woo begins to disclose how her process and product are co-dependent and co-constrictive.

The works themselves are striking in the gallery space. They are familiar through the recognisable natural patterns (tide marks on the sand, time worn formations of rocks, drying pools of water, mould or moss growth), but expressed through a foreign canvas. Macfarlane explains this familiarity of natural forms,

…nature also specialises in order and repetition. The fractal habits of certain landscapes, their tendencies to replicate their forms at different scales and in different contexts these can lend a mystical sense of organisation to a place, as though it has been build out of a single repeating unit.[2]

While not a representation of environment, Woo’s canvases convey this dual sense of scale. They are at once vast landscapes, as well as intricate geological and botanical details. Painting with Weather can almost be divided into two series, which are indirect and abstracted impressions of tidal flats and inland salt lakes. The silvery water ways and iron oxide droughts are binary sites of extreme presence and absence of water, rendered on canvas through stimulation and deactivation: flooding and evaporation.

Throughout Painting with Weather Woo has been in studio residence, and has installed an evolving exhibition in Constance Gallery. Over the month duration, the artist introduced new works to the gallery, and experimented with the display of her studies and large-scale canvases. This evolution is reflective of the dynamic relationship between artist and environment, and the process driven practice of Woo. In the second fortnight of the exhibition, Woo installed several larger pieces directly onto the gallery wall, which increased their arresting presence in the space and amplified the relationship between the smaller studies and the final works.

A study suggests a sketch or draft, but that is true of these works on insofar as they are explorative and preparatory. A shelf on the studio wall supports pieces still in development, and this structural device is mimicked in the display of finished pieces in the Main Space of the gallery next door. Woo has installed a temporary plank along one side of the wall, and in this architectural echo, the artist brings some of the studio into Constance. In the gallery, they sit above and below the shelf on the wall, which acts here like a tide line for the watermarks is supports. The studies capture an intimate quality of the larger aluminum canvases, and hint at the experimental and scientific methods informing Woo’s practice.

Catherine Woo’s work is ‘weathered’, but here the natural processes are stimulated, orchestrated, and in responsive partnership with natural forces. Her metallic artworks aren’t rusted by neglect and time, but are stimulated and experimented upon to achieve a trace of the environmental past, in the gallery present.

[1]Robert Macfarlane, The Wild Places, 2007, Grant Books, London, p. 246

[2] Ibid

23

Jan

Constance Critique no. 4

- By admin

Dirty Big Whole

Review by Bridget Hickey

Photography: Peter Mathew

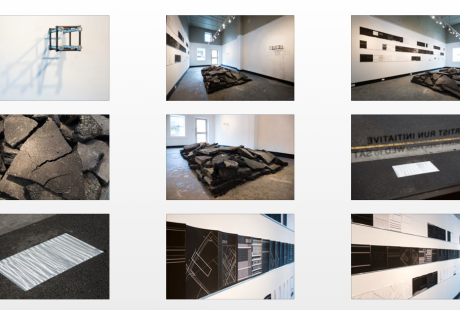

Last December, Constance Artist Run Initiative (ARI) became a construction site. Provocatively titled Dirty Big Whole, the exhibition saw the excavation of a public artwork from outside the building and the associated waste material re-presented in the gallery space. Conceived by established Hobart artists Lucy Bleach and John Vella, the show provided a complex and intelligent engagement with current issues surrounding the making of contemporary art.

Although Dirty Big Whole involved a display of objects, the exhibition is perhaps better described as a series of processes. Bleach obtained permission from the Hobart City Council to temporarily remove two sculptural aluminium bike racks, part of the Artbikes scheme funded by the Council’s Public Arts Program. Shaped like silhouetted pedestrians, the racks usually provide an unchallenging addition to the streetscape. Bleach filled the holes left by the excavation with aluminium plates, replacing figurative forms with abstracted versions. The artist also displayed the racks’ metal footings inside the gallery, transforming the functional into sculptural objects. Vella’s contribution to the show involved the presentation of paperwork relating to the gallery space, namely Arts Tasmania’s funding and acquittal forms and Bleach’s council permits. These were mounted across the length of one wall, their text blanked out. The final element of the exhibition was produced collaboratively and consisted of displaying the displaced bitumen inside the gallery. Arranged into a large but surprisingly tidy rectangle, the pile was supplemented for aesthetic effect with other material from nearby roadworks.

Bleach and Vella’s actions provide a multi-layered examination of issues surrounding the funding and support for contemporary art. On one level, the work comments on the role of permission and endorsement surrounding contemporary arts practice, and the contradiction between the ideal of artistic freedom and the need to earn a living. This is particularly true of ‘experimental’ artists, whose non-commercial work often relies on government funding and the support of arts organisations. In seeking permission to undertake a process that could be perceived as subversive, Bleach and Vella’s exhibition exposes the ironies inherent within this system. At the same time, their work successfully demonstrates the potential for this kind of practice to question and critique.

On another, related level, the show also taps into current discussion about arts funding in Tasmania specifically. December marked the start of a difficult period for Constance, as the last month before the ARI’s Assistance to Organisations grant expired. From January 2014, it will rely heavily on the generosity of the local arts community to continue as Tasmania’s longest-running ARI. Although the opening of David Walsh’s privately funded Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) has brought unprecedented opportunities and publicity to the local arts scene, its arrival has coincided with an economic downturn and a subsequent reduction in state support for the arts. In presenting a show about funding in a gallery soon to be de-funded, Bleach and Vella’s exhibition could easily be read as a clear-cut political statement. However, Dirty Big Whole chooses to aestheticise bureaucracy, to poeticise rather than polemicise. By relocating an under-utilised permanent public artwork into the more provisional space of an ARI, viewers are encouraged to question which work has more value. However, the answer is left up to the individual.

Bleach and Vella play a significant role as mentors in the local arts community, both teaching at the Tasmanian College of the Arts. With a combined exhibition history of nearly fifty years, their decision to show at Constance ARI is meaningful. While lending support and legitimacy to a space usually designated for emerging practitioners, Bleach and Vella also challenge the expected career pathway for mid-career artists and the artificial structures and expectations that can develop. More than a hole in the ground, Dirty Big Whole is a subversive and playful exhibition that examines the whole system of rules and regulations in which we all must function.

05

Dec

Constance Critique no. 3

- By admin

Nature, nurture, node

Review by Eliza Burke

Nature, nurture, node is a show with three concepts, three artists and three spaces. The show’s curator, Erin Davidson carves out a conceptual terrain that offers a range of perspectives on our contemporary relationship to nature and to our increasingly built and digital environments. Each of the artists offers a unique perspective culminating in an enriching show.

Davidson’s placement of the works throughout the three galleries creates a narrative flow from exterior to interior spaces. Thom Buchanan’s explorations of the built environment in the front space makes for an easy transition from street to gallery, and the sense of a city stripped bare. The industrial quality of these works creates a nice dialogue with the rough interior surfaces of Constance, although the installation of the works in a linear format is perhaps too clean.

In the foyer space, Meaghan Roberts’ paintings relieve the hard edges of Buchanan’s works, through a heightened sense of colour and the familiarity of landscape. Despite her reference to traditional landscape, the collisions of paint and perspectives in Roberts’ works also evoke a supernatural quality as they shift between abstractions of the microscope and more distant views.

The alien territories of Roberts’ paintings prepare the ground for Nick Smithies’ Glitch Glade installed in the closeted Paddy Lyn gallery. This work for me is the literal and conceptual core of the show, both seductive in its darkness and the promise of nurture and alienating in its uncanny mimicry of ‘natural’ space and sound.

I confess to getting stuck in Glitch Glade, fascinated with its looped simulacra and perpetual exchange of imitative and deconstructive elements. Such was the effect of this work, that on moving back through the gallery, I found Roberts’ and Buchanan’s works less actively engaged in questions of nurture or the human/nature relation. Although these questions are tentatively referenced in the threat of the catastrophic in Roberts works and the ghostly layers of Buchanan’s, I found the tripartite concept of nature, nurture, node most fully rendered in Smithies’ work.

For me, Glitch Glade gave this show a pulse. It compelled me to reflect on our capacity to tune into the rhythms of the natural world, the growing complexity of relationships between synthetic and organic experiences, and the seduction of our digital and constructed environments.

05

Oct

Constance Critique no. 2

- By admin

With bright and shiny stars in my eyes by Jessie Lumb

Words by Francisca Moenne [Kika Moen]

[…] and the stars that still sojourn, yet still move onward

S. T. Coleridge (The Rime of the Ancient Mariner)

I spoke with South Australian artist Jessie Lumb on the afternoon of the opening of her solo exhibition entitled With bright and shiny stars in my eyes in the Main Space of Constance ARI in Hobart. From this conversation I could see how her engagement with the work went way beyond the worry of a personal success, and was instead a sincere engagement with her surrounding.

Having just completed a major public artwork for Arte Magra, from the Opaque, curated by Domenico de Clario and Mary Knights through the Australian Experimental Art Foundation in Adelaide, Lumb shared with me how she engages with spaces. “I am more interested in public interventions.” Lumb told me about how in Arte Magra she had spent days painting bubble-gum on the pavement of Hindley Street in Adelaide cities most seedy area. As if restoring the bubble-gum to its original vibrant glory in bright shades of pink, purple, green, blue and orange.

Lumb’s steadiness and installation, I admit, instantly threw me into a rollercoaster of thoughts. At first, I was not able to clearly read the significance of the work she had just completed for Constance ARI. As her work requires time and distance to truly come to terms with its broad and profound significance.

As an artist and curator myself, it took me time to realise that viewing With bright and shiny stars in my eyes had unlocked a personal urgency to reconsider the relationship between the artist and space, and the curator and viewer. Lumb’s work seems to consider everyone’s viewing experience as individual. Her practice is about an artistic gesture that slowly and gently draws the viewer into a deep spatial experience with unseen aspects of the world around us. The floorsheet accompanying the exhibition suggesting where to look and what to look for, listing: “glitter glue and cardboard filling ground and ceiling craters (gallery, car park and toilets)”. The viewing experience of With bright and shiny stars in my eyes takes you on a journey. The result is a silent and poetic show.

By filling the holes of the Main Space of Constance ARI’s floor and ceiling with blue glitter paint and cardboard, the artist not only redeems the history of the building but also urges the viewer to look for the unseen. This act of looking closely at the ground and at the ceiling is not a common gallery viewing experience and catches the viewer off-guard. By drawing your focus to the holes or remains left behind from years past, Lumb’s work also acts to highlights the present. As Lumb put it: “The imperfections and history in public spaces are usually left as they are. The perfect white wall of a gallery space can be terrifying! And their perfection doesn’t give me enough material to work with”. Her work is almost a return or homage to minimalism: a conscious look at contemporary and social activism yet silent and poetic. Her work draws the viewer’s eyes to search for her work and see the world with a new perspective (perhaps with bright and shiny eyes in ones eyes?).

Throughout the first five years of her practice, Lumb has spent much time living and working with other cultures around the world. During her studies she undertook a student exchange to San Diego, in 2010 she participated in a six week residency in China and recently she has returned from twelve months in Ulaanbaatar as an Australian Young Ambassador for Development with the Arts Council of Mongolia. Now she is involved in a roaming art space called Tarpspace [http://tarpspace.com]. I wonder: is it the need for the artist to extend her surroundings? Or the need to look at different spaces? Or maybe the need to get away from todays man-made society?

Lumb’s overall arts practice seems to draw attention to the necessity to look closely at our everyday surroundings. As I have discovered by writing about this work a wider view comes hand in hand with a closer look. It was also highlighted to me that the arts need to be constantly restored and to be considered in the “here and now” knowing that “yesterday” may also have left remains behind, remains that might still need to be taken into consideration.

By using materials that are easily accessible (a trait that she might of picked up from her traveling?) it is obvious that the artists’ concerns are not material or consumer minded. Her real materials are her eyes – and this way of looking at the world around her. Her work is a process that not only considers a space but is also conscious of time. Along with this line of thinking, I can now see why her installation sent me into a rollercoaster of thoughts, and made me connect with what was then happening around me at the time.

With bright and shiny stars in my eyes resonates well with the current return to conceptual art making. It is almost as if conceptualism has not yet been fully explored and understood. Maybe this is because it hasn’t yet found a way to connect to the real sensations of our human world. Is this why we are still seeing much of Bruce Neuman’s work around the world but not really hearing his message “think think think”? Is it that we have not yet found a way to engage the conceptual with our contemporary world? Maybe we are still learning that the ultimate role of all experimental art is to contribute to the way in which we engage with the world around us.

08

Aug

Constance Critique no. 1

- By admin

MOP@Constance

Written by Lucy Hawthorne

The MOP exhibition at Constance coincides with the 10th birthday of both Artist Run Initiatives (ARIs). In February this year, Inflight ARI was relaunched as Constance to indicate a change in focus. Although some might argue that Constance is yet to turn one, it builds upon the solid base established by a decade of Inflight committee members and thus is not a new organisation, regardless of the new name. This inaugural Constance blog post will explore broadening definition and ‘lifecycle’ of the ARI in Australia, and look at changes to the Hobart ARI scene over the last decade.

Like Inflight, MOP was originally established at a different site – a small former ragtrade workspace tucked away up four flights of stairs in Redfern – before moving to its current location in Chippendale in 2008. Many years ago I wrote a rather tongue-in-cheek guide to Hobart galleries, describing Inflight’s former location as ‘challenging to find … Inflight is hidden behind the toilets, which are behind the garbage bins, behind the carpark, behind Kaos café…’ Still, there’s something romantic about the secret ARI, the exclusive ‘did you hear about…’ nature of the hard-to-find new arrival on the art block. But as ARIs mature and become integrated into the local art scene, there is a tendency to move to a new, more visible location. This is often because funding enables the move, but it also signals, as I noted, a maturity, a sign that the ARI will run a little longer than the norm. For Inflight, the move occurred seven years after its establishment, and MOP five years. I use the word ‘maturity’ because the ARI lifecycle is often described as a ‘phoenix’: one ARI dies and another rises from the ashes. The analogy is beautifully descriptive, because rather than mourn the ‘death’ of the ARI, it’s commonly acknowledged that ARIs don’t need to last forever to succeed, and that the dynamism that new ARIs bring is quite different to a ‘mature,’ more established organisation. This is not to say that the new ARI is superior to the old ARI – they’re just different, and serve different purposes. When 6a opened in North Hobart in 2007, it filled a gap in the Hobart art scene. Simultaneously, the siteless ARI, 10% Pending (of which I was a part) was formed. With its raw interior and kitchen gallery, 6a encouraged site-specific work, hosting exhibitions such as Tristan Stoward’s live-in performance and Josie Hurst’s bathtub video. 10% Pending ignored the gallery space altogether, preferring to create temporary clandestine exhibitions in public spaces. The three ARIs worked well together, and when 6a and 10% Pending wound up a few years later, Hobart definitely lost some key exhibition opportunities for emerging and experimental artists. Just prior to 6a’s closure in 2011, Inflight moved to its current location at Goulburn St. Although expensive, the gallery now has a streetfront and is visible to passers by (a sign of that before mentioned ‘maturity’?). The 6a building is still used as artist studios, and while I mourn its closure, I also see it as an opportunity for another ARI to sprout up.

It’s pretty well accepted that ARIs cater for emerging artists and experimental art practice. Most importantly, they provide alternative opportunities to the larger public institutions, such as the state galleries and the CAOs group (interestingly, many of the CAOs institutions originated as ARIs, such as Hobart’s CAST and Sydney’s Artspace). The subversive or independent nature of the artist cooperative is key to their success. Australia’s first artist run spaces, such as Inhibodress (1970-2), were established at a time of significant change in the national art scene and were a significant alternative to the then very conservative public state galleries and commercial galleries (with a few exceptions, notably Pinacotheca in Melbourne and Watters in Sydney). ARI boards are, as the name suggests, artists, and therefore it is appointed members of the local artist community who dictate the type of art exhibited. The agendas and aims of these artist groups are obviously very different to those of the large state gallery boards who have to cater for a far broader and arguably more conservative audience. However, older ARIs risk moving towards conservatism. We see more paintings on the wall, fewer mad experimental installations or performances, fewer artists with little or no exhibition history. Yet, they also move towards more diverse programming. MOP, for instance, has a commercial counterpart run by its two directors, George Adams and Ron Adams. The 20-year-old West Space has multiple arms, including writing and education programs; and Firstdraft has extended its reach since it opened in Surry Hills in 1986, more recently establishing studios and a publishing coop in Woolloomooloo.

As I noted earlier, Hobart’s art scene from 2007-2011, included three quite different ARI models. 6a and Inflight were rented spaces, and while Inflight was a more ‘neutral’ white-walled gallery, 6a encouraged art that responded to the former slaughterhouse space. Inflight has always hosted a number of programs outside the gallery space, mostly travelling exhibitions, whereas 6a had a broader program on site, supporting studios, markets and the occasional music event. 10% Pending on the other hand was site-less, which allowed it more freedom in terms of the board’s curatorial vision, event dates and sites, and most significantly, it was almost exclusively financed by cake-stalls. Siteless or mobile ARIs such as 10% Pending and the recently launched Tarpspace, reflect the broadening definition of the cooperative exhibition space, and also help explain the popularity of the term ‘artist run initiative’ as opposed to the older ‘artist run space.’

The renaming of Hobart’s now sole ARI from Inflight to Constance earlier this year was designed to communicate a significant shift in programming, specifically a new emphasis on off-site exhibitions in addition to its gallery program. However, Inflight’s excellent (pre-emptive?) satellite exhibition in Queenstown late last year, demonstrated that the name change was perhaps unnecessary because, like all older ARIs, Inflight has developed and expanded its focus over time. Inflight/Constance has supported hundreds of artists over the last decade, reflecting the commitment of the dozens of past and present board members to the organisation, as well as the support of funding bodies, writers, critics, and the local arts community. ARIs provide opportunities to emerging artists; they offer exhibition spaces that lack the ideological restrictions of the larger galleries, and their smaller, more focussed audience means that artists can present more provocative and experimental work without the rallying cries of ‘think about the children’ or ‘the Oxford English Dictionary [of 1973] defines art as…’ We need ARIs. Hobart needs ARIs, and I stress the plural. We need ARIs that work together to plug gaps in the local art scene, particularly with the recent closure of the Carnegie Gallery, and the Plimsoll Gallery’s lack of funding-induced hiatus. Over the years, Inflight has become a significant player in Australia’s ARI network, hosting exhibitions from dozens of other ARIs, including MOP (now for the second time). Regardless of the name change, I see Constance continuing this network while expanding its program to include not just off-site exhibitions but this new writing program, and this can only be a good thing.

Notes and links:

Tarpspace will be in Hobart in December 2013. For information, see: tarpspace, CAOs, MOP, Inflight, Firstdraft, Westspace and 10% Pending.

08

May

Do you want a show at Constance?

- By admin

- No Comments

CALL FOR PROPOSALS:

August – December 2013

Proposals due by COB May 17 2013

$650 per show (Main Space)

$200 per show (Paddy Lyn Space)

$200 per show (Foyer Space)

Constance, formerly known as Inflight, is calling for exhibition proposals for the second half of 2013. Now celebrating 10 years this year marks a momentous new direction. Constance provides a platform for emerging and experimental artists to push the boundaries of their existing practice for the exhibition of new and challenging work.

Artists/curators from any level of experience are encouraged to apply; however application does not guarantee acceptance and all applications will be assessed against the selection criteria below.

Selection Criteria

• Quality of recent work or work in progress, well documented

• Strength and innovation of the proposed exhibition/ project

Please include the following information in your application:

1. Cover page – include name, postal address, contact phone number and email address of a nominated contact person. Also include preferred month and exhibition space (Main, Foyer and/or Paddy Lyn Space) and proposed title for exhibition (1 A4 page).

2. CV and/or biography – please keep concise and arts related. (1 A4 page per artist)

3. Project Description – a brief description of how you envisage the proposed project in the Main, Foyer and/or Paddy Lyn Space. Indicate the scale/size of proposed work and intended use of the space(s). Mention any special requirements for install and equipment (projector, plinth, dark room etc.). (Maximum 300 words)

4. Rationale – a concise statement of the ideas and concepts informing your arts practice and how you propose to develop these further in this project at Constance. (Maximum 300 words)

5. Support material – 6 images for a solo exhibition and 12 for a group exhibition. Video or sound files must be limited to 5mins in total. Include a list of support material details with the full credit information (name, title, year, dimensions and medium). We accept emailed digital files or posted on a CD/DVD (72 DPI, 480 x 640 pixels max).

General Information

• Exhibitions run for a three-week period with a one-week turn around.

• A projector is available for hire at $50. You will need to supply your own AV gear / media player.

• Proposed exhibitions can include one, two, or all three spaces.

• Openings are concurrent; i.e. 1 opening will take place for all shows.

• Exhibiting artists are required to sit the exhibition on Saturdays or cover the cost of a sitter.

• Constance will assign a liaison officer from the Board that will correspond with and assist the artists/curators during install, exhibition period and de-install. The Director will also be available during office hours (Wed-Fri 10am-5pm).

• The Director and Board of Constance strongly encourage challenging, critical and focused discussion of exhibitions. The Director and Board of Constance coordinate public programs in correspondence with the participating artists.

Promotion and Opening

• Invitations are produced by Constance in hard-copy poster and card format and online through the Constance mailing list and partners. Priority is given to the Main Space and hard-copy invitations are not guaranteed for the Foyer or Paddy Lyn.

• Exhibitions and events at Constance are advertised on the website, Facebook, Twitter and listed in Art Almanac, Art Guide, Hobart Gallery Guide, Warp magazine and other publications.

• A bar will run at openings by the Board and volunteers.

Submit

• Hard-copy proposals and image files on CD/DVD to Constance’ postal address: GPO Box 2094, Hobart, TAS 7001

• Email proposals to: constance.director@gmail.com Clearly label all attachments preferably sent as PDF, less than 4MB. Subject email as: “PROPOSAL Aug-Dec 2013”. Note: For ease of assessment it is preferable to submit applications and support material via email formatted into a single PDF.

Contact

For more information on the gallery and other details that may assist in preparing your proposal please contact:

Polly Dance

Gallery Director

Office hours: Wed-Fri 10am-5pm

Gallery open: Wed-Sat 1-5pm

W: www.constancearchive.dreamhosters.com

E: constance.director@gmail.com

M: 0429 536 432

DOWNLOAD FLOOR PLAN

25

Apr

Hello!

- By admin

- No Comments

Welcome to Constance’s new website.

Our web designer has just welcomed an (early) baby, Sid, so stay tuned for updates, including exhibition information.